The Monty Hall Problem

Probability / brain teaser

In the 90’s there used to be a game show hosted by a guy named Monty Hall. This problem is loosely based off of his show and it’s part brain teaser and part probability question. I came across this problem a couple of years ago and why I found it interesting is that even after reading the solution to the problem, my brain just refused to believe that that was the case. It was after pondering over it for a while that I had the aaha! moment and actually understood why my initial guess was wrong. I would suggest that instead of going straight to the solution, take some time to think about it. That way you’ll be able to enjoy the problem better.

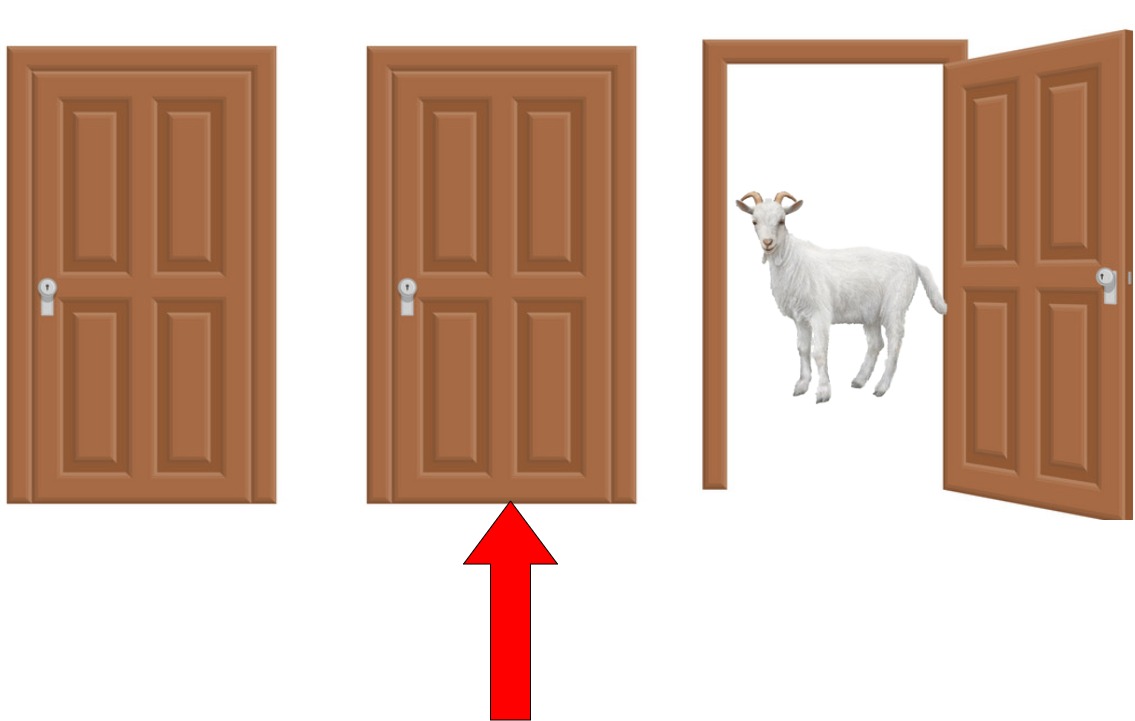

Imagine there are 3 doors. Behind 2 of these doors is a goat, and behind the third door is a car. Suppose I told you that you can choose one door, and you get to take home whatever lies behind it.

But there’s one catch. Once you make your choice, I open one of the other 2 doors and show you that there lies a goat behind it. Say you chose the door marked by the red arrow, and I opened the 3rd door revealing a goat.

Now that there are 2 doors left, the one you initially chose, and another one (the 1st door), where one of them holds a goat, and the other holds the car. If given a chance to switch your selection, should you switch?

Think about it for a moment.

Most peoples’ first intuition is that once a door with a goat is removed, there’s a 50–50 chance in between the remaining 2 doors and so, weather you choose to switch shouldn’t affect your chances of winning the car. But what if I told you that switching ALWAYS DOUBLES your chances of winning.

It isn’t that obvious at first, but on giving it some thought, it actually makes sense. There are various methods to prove this. Here I’ll show you one way of thinking about it.

The odds are clear when the initial selection is made. 3 doors, two goats and one car. There’s a 66% chance of selecting the goat, and a 33% chance of selecting the car. The magic happens when one of the other two doors is opened. It is guaranteed that the door that’s opened, has a goat behind it.

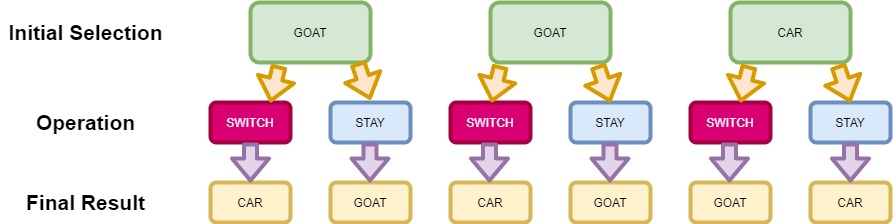

There are only 2 ways the initial selection can be made. Either we chose the car, or we chose the goat. Once this selection is made, one of the other 2 doors is opened. Now of the two remaining doors, one holds the car.

Considering just the scenario where we do choose to switch our selection. If the initial selection was a goat, then switching gets us the car. If the initial selection was the door with the car, then switching will get us the goat. Here’s where the initial probability kicks in, there’s a 66% chance of having selected a goat as the initial selection in which case, switching would get us the car. And there’s only a 33% chance of having selected the car as our initial selection, in which case, switching gets us the goat.

Hence our chances of winning the car increases from 33% to 66% if we decide to switch our selection.

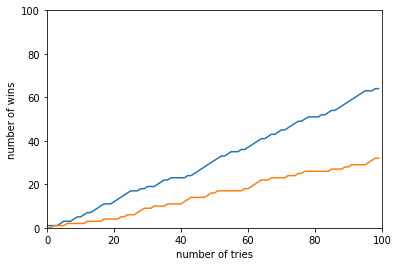

The beauty of probability is that any probabilistic result can be reproduced in real life if enough trials are made. Using python to simulate the two cases, the case where the player always chooses to switch, and the case where the player never chooses to switch.

I wrote a python snippet that takes in as arguments the number of tries to perform, and weather to choose to switch at each try. On running the code for both the cases, switching (represented in blue) and no-switching (represented in orange), the below graph shows the number of wins with respect to the number of tries.

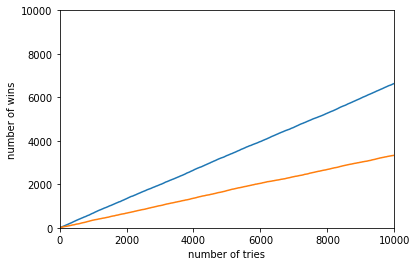

Here’s the graph for 10,000 tries and it can be seen that the number of wins when the switch is made is 100% greater than the number of wins when no switch is made.

These graphs show that if you choose to swich, there’s a 66.6 % chance of you winning the car as opposed to a mere 33.3% if you decide not to switch.

Here’s the link to the code I wrote on colab to simulate the two test cases. Monty Hall Simulation python

Lastly, here’s a tree showing all reachable states. Notice that in the case of switching, the only way to loose, is if the initial selection is a car, which has only a 1 / 3 chance of happening.

Apart from the fact that this is an interesting problem, it shows that sometimes what seems to us as a correct prediction might be in reality, far from accurate, and that using mathematical analysis when taking everyday decisions could go a long way.